What Is It Called When Someone Has a Life.sentece.but.goes.back to.fight Your Case Again

Eight Keys to Mercy:

How to shorten excessive prison sentences

By Jorge Renaud Tweet this

November 2018

Press release

Printable version

Introduction

After decades of explosive growth, prison house populations have mostly flattened. Much of that is due to lawmakers lessening penalties for drug possession or depression-level belongings offenses. While a welcome outset, a bolder approach is necessary to truly brainstorm to make a dent in the numbers of individuals who have served and will serve decades behind bars. This arroyo volition take political courage from legislators, judges, and the executive branch of country governments.

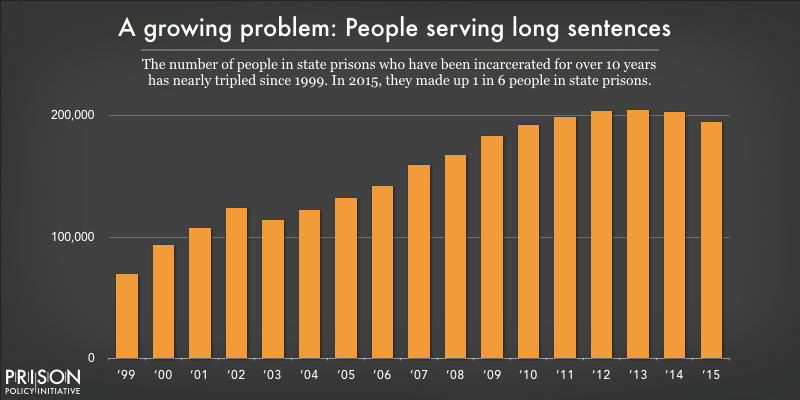

Approximately 200,000 individuals are in state prisons serving natural life or "virtual" life sentences.one And as of twelvemonth'south cease 2015, one in every six individuals in a country prison had been at that place at least for 10 years.2

These are not merely statistics. These are people, sentenced to unimaginably long sentences in ways that exercise niggling to accelerate justice, provide deterrence, or offer solace to survivors of violence. The harm done to these individuals because of the time they must practice in prison house cells - equally well as to their families and their communities - is incalculable.

People should not spend decades in prison house without a meaningful chance of release. There exist vastly underused strategies that policy makers can employ to halt, and meaningfully reverse, our overreliance on incarceration. We present 8 of those strategies below.

Understanding long prison house terms and mechanisms for release

Too many land prisons hold besides many individuals doing too much time. The goal of our eight strategies is to bring immediate relief to these individuals, by creating or expanding opportunities for their release. However, to discuss such reforms, nosotros beginning demand to understand the basic mechanisms by which someone is released from prison. In particular, information technology'due south important to accept a full general thought of how parole works.

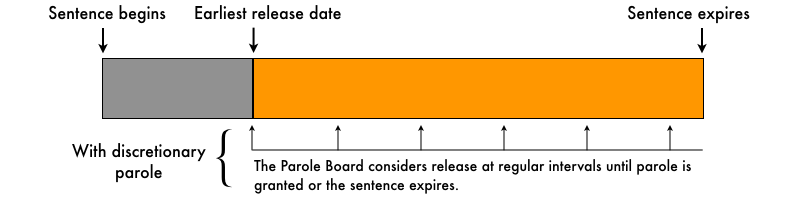

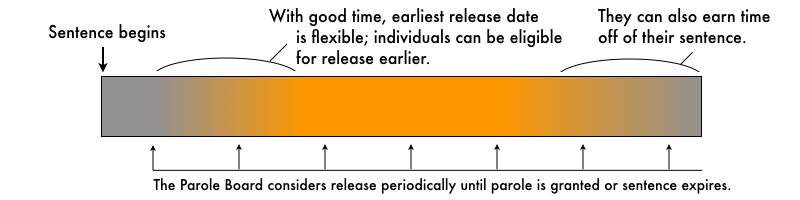

In full general, when someone is convicted of a felony and sentenced, that person loses their freedom for a period of time. A portion of this flow is typically served in a prison, and ofttimes a portion is served in the community under supervision, too known as parole.3 When parole boards have discretionary power, they periodically review someone's example to decide if they should be released, first on their primeval release engagement. (One's earliest release appointment may be well before the end of their penalty, or close to the terminate of their punishment, depending on country- specific statutes and requirements prepare by the judge.4)

For instance, someone bedevilled of aggravated robbery might be sentenced to a maximum of 30 years in prison house, and in about states would be eligible for release after a sure period of time, let's say 10 years.8 At that 10-year mark, this individual reaches their earliest release date, and the parole board considers their release on parole for the first fourth dimension. If non released on parole, the parole board continues to consider release at regular intervals until that person is granted parole or maxes out their sentence.

Our viii strategies

The viii suggested reforms in this report can shorten time served in different ways:

- Several means to make people eligible for release on parole sooner.

- One way to make it more probable that the parole board will approve conditional release on parole.

- Several means to shorten the time that must be served, regardless of sentencing and parole decisions.

- One simple way to ensure that people are not returned to prison.

Of course, states vary in many means, about critically in how they structure parole eligibility (see sidebar above), and policymakers reading this report should anticipate tailoring our suggested reforms to their country systems. Each of the reforms laid out in this written report could exist effective contained of the others. However, we encourage states to use as many of the post-obit tools as possible to shorten excessive sentences:

- Presumptive parole ⤵

- Second-look sentencing ⤵

- Granting of good fourth dimension ⤵

- Universal parole eligibility afterward xv years ⤵

- Retroactive application of sentence reduction reforms⤵

- Emptying of parole revocations for technical violations ⤵

- Compassionate release ⤵

- Substitution ⤵

Presumptive parole

Presumptive parole is a system in which incarcerated individuals are released upon first becoming eligible for parole unless the parole board finds explicit reasons to not release them. This approach flips the electric current parole approach on its head, so that release on parole is the expected event, rather than one that must be argued for. Nether this framework, an incarcerated person who meets certain preset conditions will automatically exist released at a predetermined date.

Currently, parole boards treat continued confinement as the default and must justify why someone should be released. Logically, parole should but be denied if the board tin can evidence that the individual has exhibited specific behaviors that indicate a public safety risk (repeated tearing episodes in prison, refusal to participate in programming, aggressive correspondence with the victim, etc). Merely parole board members - who are well-nigh exclusively gubernatorial appointees - may lose their jobs for merely considering to release someone sentenced to life,17 or for releasing someone who unexpectedly goes on to commit some other crime.18 Equally a consequence, many parole boards and their controlling statutes routinely stray from show-based questions almost prophylactic (run into sidebar, right).

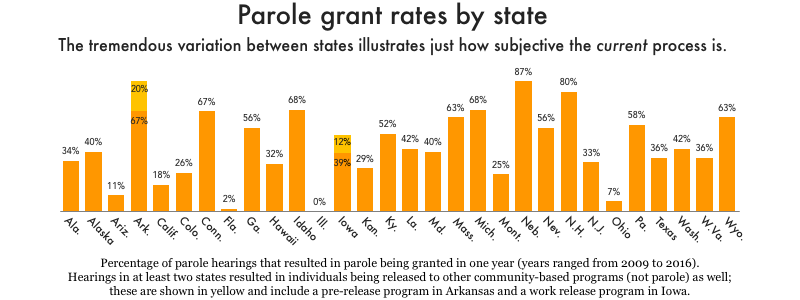

The subjectivity of the electric current procedure is powerfully illustrated by the tremendous variations in the charge per unit at which states grant parole at parole hearings, which vary from a high of 87% in Nebraska to a low of 7% in Ohio, with many states granting parole to just 20% to 30% of the individuals who are eligible.

An effective parole organisation that wants people to succeed volition get-go with the assumption that success is possible. Instead of asking "why" the parole lath should believe in the person coming before them, information technology should ask "why not" allow that person go, then outline a plan that includes in-prison house program participation and post-release customs-based programming to assist the potential parolee overcome barriers to release.

Irresolute this presumption would also create powerful new incentives for the entire organization. The Department of Corrections would have an incentive to create meaningful programs, and incarcerated people would have an incentive to enroll and successfully complete them.

An effective presumptive parole arrangement would take elements like those often found in Mississippi, New Jersey, Michigan, and Hawai'i:

- Give clear instructions to incarcerated people on what they demand to do in social club to be released on a specific date.

- Give clear instructions to incarcerated people, if they are denied release, on what they demand to practice to exist released at the side by side hearing.

- Require re-hearings in no more one or 2 years.19

- Provide case managers to assistance incarcerated people develop a plan to be successful at parole decision time.

- Provide transparency to incarcerated people by sharing as much information every bit possible nigh how the parole lath reached its decision.twenty

- Provide transparency and accountability to the legislative branch by requiring annual reports on the numbers of, and reasons for, denials of parole, especially denials of individuals whose release has been recommended past guidelines supported by validated risk assessments.

Of form, those four state models have limitations that other states should be cautious about repeating:

- Limiting presumptive parole to only certain offenses or for sure sentences. 21

- Allowing parole boards to prepare aside official guidelines and deny release for subjective reasons.22

2nd look sentencing

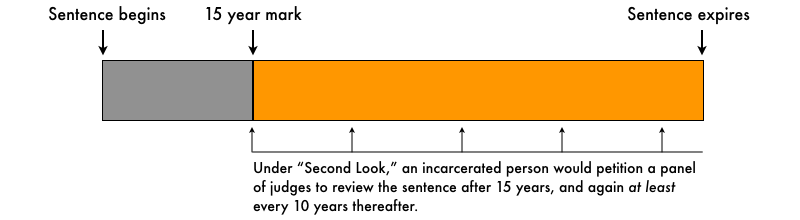

Second-look sentencing provides a legal mechanism for judges to review and change private sentences. The most effective way to do this is described in the newly revised Model Penal Code, published by the American Law Plant.23

The Model Penal Code recommends a procedure by which long sentences are automatically reviewed past a panel of retired judges after 15 years, with an eye toward possible sentence modification or release, and for subsequent review inside 10 years, regardless of the judgement'south minimum parole eligibility appointment.24 This proposal also requires that country Departments of Corrections inform incarcerated people of this review, and provide staff resources to assist them set up for it.

To be sure, many states may accept statutes that permit sentencing judges to reconsider an original sentence, although except for in Maryland,25 this doesn't happen very often.

The reality is that people and societies change, every bit practise views about punishment. Second-look provides the opportunity for judges to weigh the transformation of an incarcerated private against the perceived retributive benefit to society of 15 years of incarceration.

Second-look is the simply proposal in this report in which the judiciary would play a leading office, and that makes it particularly powerful tool in a reformist toolkit because polls bear witness that people trust the judiciary much more than they trust the legislative or executive branches of regime.26

Granting of good time

States can award credit to incarcerated individuals for obeying prison house rules or for participating in programs during their incarceration. Commonly called things like "skillful time," "meritorious credit" or something like, these systems shorten the time incarcerated people must serve before becoming parole eligible or completing their sentences.

States are unnecessarily frugal in granting good time and irrationally quick to revoke it. Good time should exist granted to all incarcerated individuals, regardless of conviction and independent of program participation. Prisons should refrain from revoking accrued practiced time except for the almost serious of offenses, and later on five years, whatever good time earned should be vested and immune from forfeiture.

Equally the proper noun implies, good time is doled out in units of time. Good time systems vary between states, as the National Briefing of State Legislatures has previously discussed.27 In some states, the boilerplate corporeality of adept time granted is negligible (North Dakota) or non-existent (Montana and Southward Dakota.) But in others, administrators are empowered by statute to laurels far more than. For example:

- Alabama can accolade upwardly to 75 days for every thirty days served;

- Nebraska tin can honor half-dozen months per twelvemonth of sentence, and can grant an additional 3 days per month for clean disciplinary records;

- Oklahoma can honor upwardly to 60 days a month, plus boosted credits for various kinds of positive disciplinary records, and a number of 1-time grants for various educational or vocational accomplishments.

Procedures will vary by land and incarcerated people may not automatically be awarded the statutorily authorized maximum. In Texas, for example, the statute authorizes up to 45 days per 30 served, but the more typical amount awarded is thirty, with the full amount reserved for people with non-violent sentences assigned to work outside the fence or in close proximity to correctional officers.

The well-nigh robust good fourth dimension systems will:

- Make skilful time eligible to every incarcerated person regardless of conviction, and ensure that every incarcerated person can employ good time toward initial parole or discharge. (For instance, Rhode Island prohibits individuals convicted of murder, sexual assault, child molestation, or kidnapping a minor from earning adept time. And while Texas allows all individuals to earn expert time, people with certain convictions are not allowed to apply it in the just two ways immune - to lessen the time they must serve earlier initial parole eligibility or to shorten their bodily time served.)

- Fully fund whatsoever programs in which participation can outcome in receiving expert time. For case, if drug treatment or educational classes make someone eligible for boosted good time credits, in that location should not be a pregnant waiting list.28

- Avert the common pitfall of restricting valuable rehabilitative programs to merely those close to release and low-gamble and justifying those restrictions past pointing to lean budgets. This runs contrary to best practices, which say that "targeting high-hazard offenders for intensive levels of handling and services has the greatest effect on recidivism, and low-risk inmates should receive minimal or even no intervention."29

- Grant boosted good fourth dimension to people who are physically or mentally unable to take reward of a program that gives good time. Many incarcerated people are mentally or physically incapable of engaging in programs, and anyone in that category should be awarded the maximum offered to those who can engage in programs.

- Let proficient time to exist forfeited only for serious rule and law violations and allow forfeited adept time to exist restored. Texas, for example, prohibits the restoration of forfeited good time,xxx while Alabama allows restoration by the Commissioner of the land Section of Corrections upon the warden'southward recommendation.31 Finally, states should not allow one incident to result in a loss of good-time accrued over years, by vesting earned good-time afterward a sure period. We again rely on the Model Penal Code, which suggests adept-time credits earned over five years be vested and untouchable.

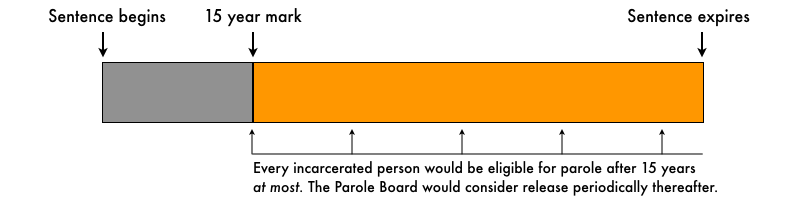

Universal parole eligibility subsequently 15 years

While many states volition retain the option of imposing long sentences, their sentencing structures should presume that both individuals and society transform over time. This proposal uses the same 15-year timeline as proposed past the Model Penal Code for Second Await Sentencing discussed higher up.32

States will vary in how they structure sentences and how parole eligibility is calculated, but states should ensure that people are not serving more than fifteen years without being considered for parole.

Retroactive application of judgement reduction reforms

Sentences are determined based on the laws in identify at the time the criminal offense was committed. Unfortunately, when sentencing reform is achieved, it almost always applies merely to time to come convictions. This means people currently incarcerated experience diff justice and neglect to benefit from progressive reform. Our statutes should be kept current with our most evolved agreement of justice, and our ongoing punishments similar incarceration should always be consistent with that progress, regardless of when the judgement was originally imposed.33

For example, 1 significant sentencing reform that was not made retroactive was Congress' modifications to the Anti-Drug Abuse Human activity of 1986, which created the infamous cleft cocaine/powder cocaine disparity that treated possession of small-scale amounts of crack cocaine as equivalent to possession of 100 times as much powder cocaine. Congress recognized that this constabulary was based on irrational science and resulted in disproportionate arrests for people of color and changed it in 2010, but the reform was for new drug crimes only. People sentenced under the one-time police force were forced to continue to serve sentences that were now considered unjust.34

Delaware passed a justice reform package in 2022 that not merely reformed three- strikes laws only allowed those convicted on three-strikes statutes to apply for a modification of their sentences. Delaware took the common-sense step of making its reforms retroactive, but far too few legislatures exercise.

Historically, when sentencing reforms do grant relief to individuals already serving lengthy sentences, it is more frequently the upshot of a judicial order. (Courts make their decisions retroactive either by requiring states to change their laws, or by having u.s.a. erect frameworks for incarcerated people to apply for resentencing.)

For instance:

- When the U.S. Supreme Court reversed an earlier decision and declared in 1963 that it was unconstitutional to put poor people on trial without start appointing them a lawyer, the Supreme Court ignored the State of Florida's plea to not make the ruling retroactive.35 The Supreme Court did so knowing that it would apply to many thousands of people serving prison sentences in v southern states, including a substantial portion of Florida's prison population.36

- In 2002, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed its earlier decision and, in Atkins v. Virginia barred the execution of the intellectually disabled — the Court used the term "mentally retarded" — instructing that the 8th Amendment's prohibition confronting cruel and unusual punishment should be interpreted in light of the "evolving standards of decency that marker the progress of a mature social club."37 The Court did not ascertain "mentally retarded," leaving each state to devise its own standards. Over the next 11 years, at least 83 individuals condemned to die instead had their sentences reduced because of a finding of "mental retardation" stemming from Atkins.38

- The Supreme Court has fabricated other improvements in sentencing retroactive every bit well, including barring execution for offenses committed before age 1839 and disallowment mandatory life without parole sentences for offenses committed earlier age 18.xl

- State courts have too fabricated changes retroactive. For example, in 2012 the Maryland Court of Appeals ruled in Unger v. Maryland that that jury instructions in upper-case letter murder convictions prior to 1981 were flawed and ordered new trials for the approximately 130 individuals still incarcerated with life sentences. (Most of those people were released by the state and placed on probation to swell success.)

Emptying of parole revocations for technical violations

Parole supervision should focus on strengthening ties between individuals on parole and their communities. Unfortunately, the emphasis is more oft on pulling parolees out of the community and returning them to incarceration at the outset sign that they are struggling,41 with parole officers intent on "catching mistakes through surveillance and monitoring, rather than on promoting success via rehabilitation and support."42 Parole officers have the power to return people to prison for "technical violations" that represent no threat to public rubber and may simply indicate that a person on parole needs more assistance, or less stringent rules, not more than incarceration.

Approximately lx,000 parolees were returned to state prisons in 2022 not because they were convicted of a new offense, simply because of a "technical violation" such as missing a meeting with a parole officeholder or traveling to some other land to visit a relative without permission. (Parole officers in Massachusetts can fifty-fifty re-incarcerate a parolee if they believe the person "is about to" engage in criminal behavior.43) For people who have already served years in prison and worked difficult to earn their release, states should make certain that parole officers are supporting their reentry, rather than sending them dorsum.

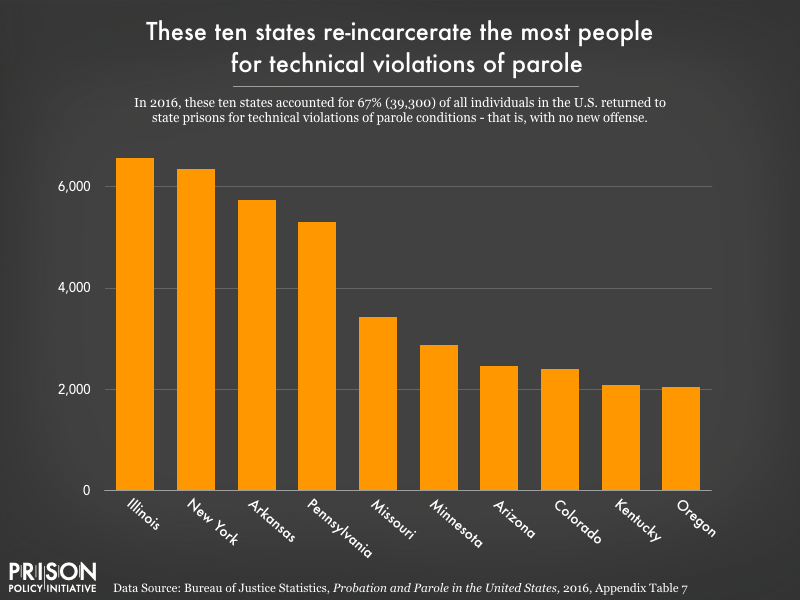

Parole revocations for technical violations are a problem in most states, but 10 states in particular were responsible for a majority of such revocations in 2016:

States should terminate putting parolees backside confined for behaviors that, were the individual not on parole, would not warrant prison time. If a parole condition is itself a law violation, it tin be dealt with by the criminal justice system. For example, a parole condition mutual to all states prohibits parolees from possessing firearms. Since states go far a criminal offense to be a felon in possession of a firearm, traditional criminal justice procedures tin can be brought to conduct when a parolee is establish with a firearm. All other, non-criminal violations should be addressed through community intervention and should never bailiwick someone on parole to re-incarceration.

Some states take peachy intendance to avoid sending people to prison house on technical violations, but other states allow high rates of re-incarceration. In lodge to increase the likelihood that individuals on parole succeed, and to lighten the load on overwhelmed parole officers, states should adopt suggestions advanced by the Robina Institute44 and Columbia University Justice Lab:45

- "Forepart-load" supervision resource immediately after release, when individuals released from prison are well-nigh likely to demand support;

- Tailor conditions to individual parolees instead of using boiler-plate language intended to embrace every possible situation;

- Limit the length of time an individual can be on parole regardless of judgement, and shorten parole terms by granting good-time for compliance with conditions.

Empathetic release

Compassionate release is the release of incarcerated individuals, usually just not exclusively anile, who are typically facing imminent expiry, and who pose no threat to the public. This process is often lengthy and cumbersome, which is unfortunate given that people recommended for compassionate release are near always terminally ill or profoundly incapacitated and the complicated nature of this procedure means many dice earlier their cases are resolved.46

All states just Iowa have a framework for compassionate release, but currently few states use compassionate release to a meaningful caste.47 The processes vary tremendously, but the basic framework is the aforementioned: An incarcerated person is recommended for release48 on empathetic grounds to prison administrators, who then solicit a medical recommendation, and and so administrators or members of the parole lath approve or deny a provisional release. These programs are plagued by many shortcomings, including:

- Requirements that a person be extremely shut to death, or so incapacitated that they do not empathize why they are being punished.49

- Requiring medical professionals to attest that someone is within six months, or ix months, of death. Health professionals are reluctant to give such exact prognoses, which ways prison officials will default to the "information technology's safer only to not permit this person go."50

- Assuasive prison personnel to overrule medical prognoses.51

To exist sure, some states exercise certain facets of empathetic release better than others, but states would be wise to implement the recommendations52 of the Model Penal Code on compassionate release, along with FAMM's excellent suggestions.53 Particularly robust empathetic release systems will:

- Exist bachelor to all incarcerated people regardless of the underlying offense.

- Streamline all processes and set reachable deadlines so that petitioners don't die due to bureaucratic bottlenecks before they are released.

- Limit the ability of prison officials to overrule, on medical grounds, a recommendation of release by medical professionals.

Commutation

Commutations are modifications of a sentence by the executive co-operative to either make someone eligible for release before they otherwise would exist, or to release them outright. These decisions are normally fabricated by the governor, or some combination of the governor and a lath, whose members are themselves oftentimes appointed by the governor. (For a detailed description of the process and structure in each country run across The Criminal Justice Policy Foundation's helpful summary.)

The procedures are often very similar, but the outcomes vary greatly between the states. Typically, an incarcerated individual submits a petition to the governor'due south office, who reviews the petition or forrard information technology to whatsoever board must make the initial recommendation. At that point, the petition is approved or denied based on whatsoever criteria that land uses.

There is not a comprehensive information source on the numbers of commutations granted across the 50 states, but it appears that clemency in general and commutation in detail are used far less than they have been in years by.56 Notable recent exceptions are quondam Illinois Gov. George Ryan (R), who in 2003 commuted the decease sentences of all 167 individuals on death row to either life or a sentence of years, and Mike Huckabee (R), who as Arkansas governor issued 1,058 acts of charity, many of them commutations and pardons to individuals with violent crimes.

Executives should consider using commutation in a broad, sweeping manner to remedy some of the extremes of the punitive turn that led to mass incarceration. Many executives have the power to shorten the sentences of large numbers of incarcerated individuals or to release them birthday. Information technology will exist tempting for governors to take circumspection from President Barack Obama's methods,57 which were bogged down by bureaucratic, structural and political cautiousness. We advise following the unique strategies of President Gerald Ford, who granted clemency to tens of thousands of men for evading the Vietnam State of war.58

Conclusion

If states are serious about reversing mass incarceration, they must be willing to leaven retribution with mercy and accost the long sentences imposed during more punitive periods in their state'due south history. This report provides state leaders with eight strategies to shorten overly long prison sentences. All that is left is the political will.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, not-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader damage of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. The organization is known for its visual breakdown of mass incarceration in the U.S., as well every bit its data-rich analyses of how states vary in their apply of penalisation. The Prison Policy Initiative's research is designed to reshape debates around mass incarceration by offering the "big flick" view of critical policy issues, such every bit probation and parole, pretrial detention, and reentry outcomes.

About the author

Jorge Renaud is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative. He holds a Masters in Social Work from the University of Texas at Austin. His piece of work and research is forever informed by the decades he spent in Texas prisons and his years as a community organizer in Texas, working with those virtually affected by incarceration.

Acknowledgements

This study would not take been possible without the expertise and input of many individuals. Laurie Jo Reynolds, Shaena Fazal, and Nora Demleitner offered crucial looks at parole systems during early drafts; and Alex Friedmann, Bernadette Rabuy, Eric Lotke, Janice Thompson, and Lois Ahrens all gave invaluable feedback. I am particularly indebted to Margaret Love for her work on commutations and pardons, Patricia Garin for providing leads on academic articles, to John Cooper of Rubber and Merely Michigan for keeping me updated about criminal justice reforms in that land, to Families Against Mandatory Minimums for their excellent work on compassionate release, and to Edward East. Rhine of the Robina Constitute of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice, both for his scholarship there and for taking time to provide clarity about parole in all l states. Special thanks to Peter Wagner for offering much-needed clarity and shaping, to Wanda Bertram for editing, to Wendy Sawyer for visionary graphics, and to the residuum of my colleagues at the Prison Policy Initiative.

Appendix

States vary widely in their use of long sentences, their release systems, and their appetites for reform. For land advocates, journalists and policymakers looking for more individualized data, we take compiled fact sheets for all 50 states. See your state:

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Bailiwick of jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- Due north Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Isle

- South Carolina

- Southward Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Virginia

- Vermont

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming

Table i. The tabular array beneath provides the data behind near of the graphics in this written report and the fact sheets above. In some places in the study or fact sheets, we accept selected a mutual reference point that allows us to compare all fifty states (for case, 2005 as a starting point when measuring change over time). However, many states have information first at earlier or afterwards points in the same data sources; this table includes the earliest available data for each state rather than the common reference points used elsewhere to compare states.

| Country | Full individuals with at least 10 years in prison, 2015 | Per centum change, total individuals with at least ten years in prison from Yr Began* date through 2015 | Year Began | Percent of total country prison population who were individuals with at least 10 years in prison, 2015 | Percent change, percentage of total state prison population who were individuals with at least x years in prison from Yr Began* through 2015 | Total parole population, 2016 | Total returns to incarceration, 2016 | Number of individuals returned to prison for technical violations, no new offense, 2016 | Percent of all returns to prison house that were technical violations, no new offense, 2016 | Does the state'south parole lath decide release date? | Percentage of individuals who were eligible for parole whose release was granted in 2014. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 4,853 | 39% | 2007 | 18% | v% | 8,150 | 473 | 58 | 12% | Yeah | 34% |

| Alaska | 331 | -3% | 2002 | nine% | -5% | 2,100 | 559 | 369 | 66% | Yes | twoscore% |

| Arizona | iii,516 | 161% | 2000 | eight% | 2% | 7,379 | 2,488 | ii,472 | 99% | Not since 1994 | xi% |

| Arkansas | 2,510 | 129% | 2001 | 16% | xi% | 22,910 | 6,003 | 5,741 | 96% | Aye | 67% |

| California | 33,629 | 75% | 1999 | 26% | 14% | 86,053 | Non since 1977 | 18% | |||

| Colorado | 2,599 | 116% | 2000 | xiii% | 6% | ix,953 | three,226 | two,397 | 74% | Yes | 26% |

| Connecticut | 1,506 | 103% | 2000 | 14% | 8% | 2,939 | 878 | 0 | 0% | Yeah | 67% |

| Delaware | 727 | 57% | 2009 | 14% | 5% | 425 | eight | 6 | 75% | Not since 1990 | northward/a |

| Florida | 17,444 | 172% | 1999 | 18% | eight% | 4,611 | 1,101 | 764 | 69% | Not since 1983 | 0% |

| Georgia | 8,667 | 186% | 1999 | 17% | 9% | 24,413 | 2,561 | 22 | 1% | Yeah | 56% |

| Hawaii | n/a | 0% | 1,479 | 336 | 336 | 100% | Yes | 32% | |||

| Idaho | 617 | 27% | 2010 | 9% | two% | 4,875 | 379 | 0 | Yes | 68% | |

| Illinois | six,506 | 122% | 1999 | 14% | 7% | 29,629 | 8,340 | 6,570 | 79% | Not since 1978 | 0% |

| Indiana | 3,183 | 87% | 2002 | 12% | iv% | 9,420 | 2,374 | ane,985 | 84% | Not since 1977 | northward/a |

| Iowa | ane,089 | -36% | 2001 | 12% | -11% | 5,901 | 1,502 | 789 | 53% | Yes | 51% |

| Kansas | 1,349 | seven% | 2011 | fourteen% | 0% | iv,331 | 162 | 0 | 0% | Not since 1993 | 29% |

| Kentucky | i,770 | 108% | 2000 | eight% | 3% | 16,536 | 6,210 | two,093 | 34% | Yes | 52% |

| Louisiana | 6,915 | 74% | 2002 | twenty% | 5% | 31,187 | 4,067 | 1,232 | 30% | Yes | 42% |

| Maine | 177 | -1% | 2012 | 8% | -1% | 21 | 1 | 0 | 0% | Not since 1976 | n/a |

| Maryland | 4,010 | 27% | 2000 | 20% | 7% | 10,887 | 1,009 | 516 | 51% | Yes | 40% |

| Massachusetts | 1,761 | 8% | 2009 | 19% | four% | 1,995 | 490 | 408 | 83% | Yes | 63% |

| Michigan | 9,656 | lx% | 1999 | 19% | six% | Yes | 68% | ||||

| Minnesota | 805 | 223% | 2000 | 8% | iv% | 6,810 | iii,182 | 2,883 | 91% | Not since 1982 | northward/a |

| Mississippi | ii,965 | 216% | 2000 | 16% | x% | 8,424 | 2,013 | 0 | 0% | Yes | n/a |

| Missouri | iv,500 | 95% | 2000 | fourteen% | 6% | 17,657 | 6,613 | iii,439 | 52% | Aye | n/a |

| Montana | 294 | sixteen% | 2010 | 16% | 6% | 1,092 | 228 | 206 | ninety% | Yep | 25% |

| Nebraska | 581 | 68% | 2000 | 11% | 2% | ane,050 | 429 | 416 | 97% | Aye | 87% |

| Nevada | i,875 | 35% | 2008 | xiv% | 3% | v,507 | 1,219 | 525 | 43% | Yes | 56% |

| New Hampshire | 301 | 8% | 2011 | 11% | 0% | 2,451 | 797 | 797 | 100% | Aye | 80% |

| New Jersey | 3,058 | 44% | 2000 | 14% | vii% | 15,180 | ane,485 | 1,387 | 93% | Aye | 33% |

| New Mexico | 743 | 65% | 2010 | 10% | 4% | two,763 | one,644 | 1,172 | 71% | Non since 1979 | n/a |

| New York | 8,812 | 52% | 1999 | 17% | 9% | 44,562 | 9,736 | half-dozen,362 | 65% | Yes | due north/a |

| North Carolina | 6,025 | 107% | 2000 | 17% | 7% | 11,744 | 1,328 | 397 | xxx% | Non since 1994 | n/a |

| North Dakota | 75 | 142% | 2002 | 4% | 2% | 634 | 311 | 239 | 77% | Yes | n/a |

| Ohio | 8,007 | 49% | 1999 | 15% | 3% | xviii,284 | ane,722 | 127 | 7% | Not since 1996 | vii% |

| Oklahoma | 3,989 | 36% | 2000 | 14% | 1% | ii,116 | 24 | 10 | 42% | Yes | n/a |

| Oregon | one,718 | 87% | 2001 | 12% | 4% | 24,077 | two,906 | 2,041 | 70% | Not since 1989 | n/a |

| Pennsylvania | 7,856 | 108% | 1999 | xvi% | 5% | 112,351 | xi,595 | 5302 | 46% | Yep | 58% |

| Rhode Island | 262 | 114% | 2000 | ten% | 3% | 441 | 49 | 41 | 84% | Yeah | n/a |

| South Carolina | 4,191 | 135% | 2000 | 20% | 11% | 4,963 | 244 | 212 | 87% | Yes | n/a |

| Due south Dakota | 425 | 7% | 2013 | 12% | 1% | two,673 | 834 | 583 | seventy% | Yes | n/a |

| Tennessee | iv,712 | 120% | 2000 | fifteen% | 6% | 13,063 | i,591 | 704 | 44% | Yep | n/a |

| Texas | 23,233 | 37% | 1999 | 15% | 3% | 111,892 | 7,142 | 1,273 | 18% | Yes | 36% |

| Utah | 436 | 100% | 2000 | vii% | 3% | 3,502 | 1,821 | 1,547 | 85% | Aye | n/a |

| Vermont | 20 | 185% | 2003 | 1% | -iii% | 1,083 | Yes | n/a | |||

| Virginia | 7,489 | 16% | 2009 | 21% | ii% | one,576 | 140 | 35 | 25% | Not since 1995 | northward/a |

| Washington | two,474 | 148% | 2000 | 14% | 7% | eleven,131 | 1,728 | 760 | 44% | Not sinc 1994 | 42% |

| West Virginia | 936 | 47% | 2006 | 15% | 4% | 3,123 | 330 | 272 | 82% | Yep | 36% |

| Wisconsin | 3,610 | 315% | 2000 | 16% | 12% | twenty,241 | 5,424 | 3,280 | sixty% | Not since 2000 | northward/a |

| Wyoming | 234 | 25% | 2006 | 10% | 1% | 783 | 160 | 133 | 83% | Yes | 63% |

| MEAN | 86% | 57% | 42% |

- Total individuals with at least ten years in prison house, 2015

- Number of individuals in a land prison for at to the lowest degree 10 years at the cease of 2015. Source: Agency of Justice Statistics, National Corrections Reporting Program, 1991-2015: Selected Variables, Year-Terminate Population. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-Academy Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2018-03-02

- Percent change, total individuals with at least 10 years in prison from Yr Began* appointment through 2015

- Modify in the number of individuals held in a state prison for at least 10 years, commencement in 2005 through the stop of 2015. Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics. National Corrections Reporting Program, 1991-2015: Selected Variables, Year-Stop Population. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Inquiry [benefactor], 2018-03-02

- Twelvemonth Began

- The yr that each land in chart began collecting data as to the number of individuals who had served at least x years in prison. Source: Agency of Justice Statistics. National Corrections Reporting Program, 1991-2015: Selected Variables, Twelvemonth-End Population. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Inquiry [distributor], 2018-03-02

- Pct of total state prison population who were individuals with at least x years in prison, 2015

- Individuals with at least x years in prison house as a percentage of the unabridged state prison population at the end of 2015. Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics. National Corrections Reporting Program, 1991-2015: Selected Variables, Year-Finish Population. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2018-03-02

- Percentage modify, pct of full state prison house population who were individuals with at least 10 years in prison from Yr Began* through 2015

- Pct change of individuals with at least 10 years in prison as a percentage of the entire state prison population, as compared with that same population when that state began collecting that information. Source: Agency of Justice Statistics. National Corrections Reporting Program, 1991-2015: Selected Variables, Twelvemonth-End Population. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2018-03-02

- Full parole population, 2016

- The number of adults on parole in a given country on Jan. one, 2016. Source: Agency of Justice Statistics, Probation and Parole in the The states, 2016, Appendix Table 5.

- Total returns to incarceration, 2016

- The number of individuals who were on parole in a given land and returned to prison house for one) a new offense, 2) a revocation of parole on a technical violation, no new offense; 3) for treatment, and 4) unknown/other. Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Probation and Parole in the United States, 2016, Appendix Table 7.

- Number of individuals returned to prison for technical violations, no new offense, 2016

- The number of individuals a state returned to prison for a violation of atmospheric condition of parole without convicting them of a new, separate offense. Source: Agency of Justice Statistics, Probation and Parole in the United States, 2016, Appendix Table vii.

- Percent of all returns to prison that were technical violations, no new offense, 2016

- The individuals that a state returned to prison for a violation of conditions of parole every bit a pct of all individuals on parole who were returned to prison house. Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Probation and Parole in the United States, 2016.

- Does the state'due south parole board determine release date?

- Whether or not a state has statutorily done away with indeterminate sentencing and does not accept a parole lath with the power to grant discretionary parole. Source: E. E. Rhine, A. Watts, and K. R. Reitz. (2018) "Parole Boards within Indeterminate and Determinate Sentencing Structures." Robina Institute of Criminal Police force and Criminal Justice. University of Minnesota.

- Percentage of individuals who were eligible for parole whose release was granted in 2014.

- The number of individuals who were granted release by a state's parole board as a per centum of the number of incarcerated individuals in that state who were eligible for parole and reviewed for parole. Source: Mariel E. Alper. (2016) "By the Numbers: Parole Release and Revocation Across 50 States." Robina Plant of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice. Academy of Minnesota.

bowieseliestionce.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/longsentences.html

0 Response to "What Is It Called When Someone Has a Life.sentece.but.goes.back to.fight Your Case Again"

Post a Comment